FCAS at Risk: Dassault Calls Out Dysfunction in Europe’s €100B Fighter Project

Dassault CEO fires a direct shot at FCAS—Europe’s sixth-generation fighter aircraft program led by Dassault, Airbus Defence and Space, and Indra—calling it “very difficult” and mired in bureaucratic gridlock. Tensions rise and timelines slip - FCAS may be flying into turbulence.

Berlin/Paris — Europe’s multi-billion-euro sixth-gen fighter dream is veering into bureaucratic turbulence. The Future Combat Air System (FCAS), jointly led by France’s Dassault Aviation, Germany’s Airbus Defence and Space, and Spain’s Indra, is facing fresh doubt about its timeline and long-term feasibility after damning remarks by Dassault CEO Éric Trappier.

Speaking to France’s National Assembly on April 9, Trappier condemned the governance model as “very difficult,” saying consensus-driven decision-making has become a technical liability.

“We cannot divide the work as we see fit. Every decision is subject to negotiation. This model slows down development and complicates coordination.” Éric Trappier, CEO at Dassault

FCAS System Failure? The Case Against Consensus

Currently in its €3.2 billion Phase 1B, FCAS is set to deliver a prototype by 2028–2029 and aims for full capability by 2040. But with the F-35 acquisition by Germany advancing in parallel, analysts suspect FCAS may be losing altitude politically.

“You can’t build a fighter jet by committee,” said one source close to the project. You can build a PowerPoint deck. Maybe.

That’s the central issue: equal-share governance has created a system where nothing moves without unanimous approval of Dassault (France), Airbus Defence and Space (Germany), and Indra (Spain). So far, that includes delays in major decisions, friction over workload, and polite political stonewalling disguised as process.

Airbus Reassures, Subsystems Progress

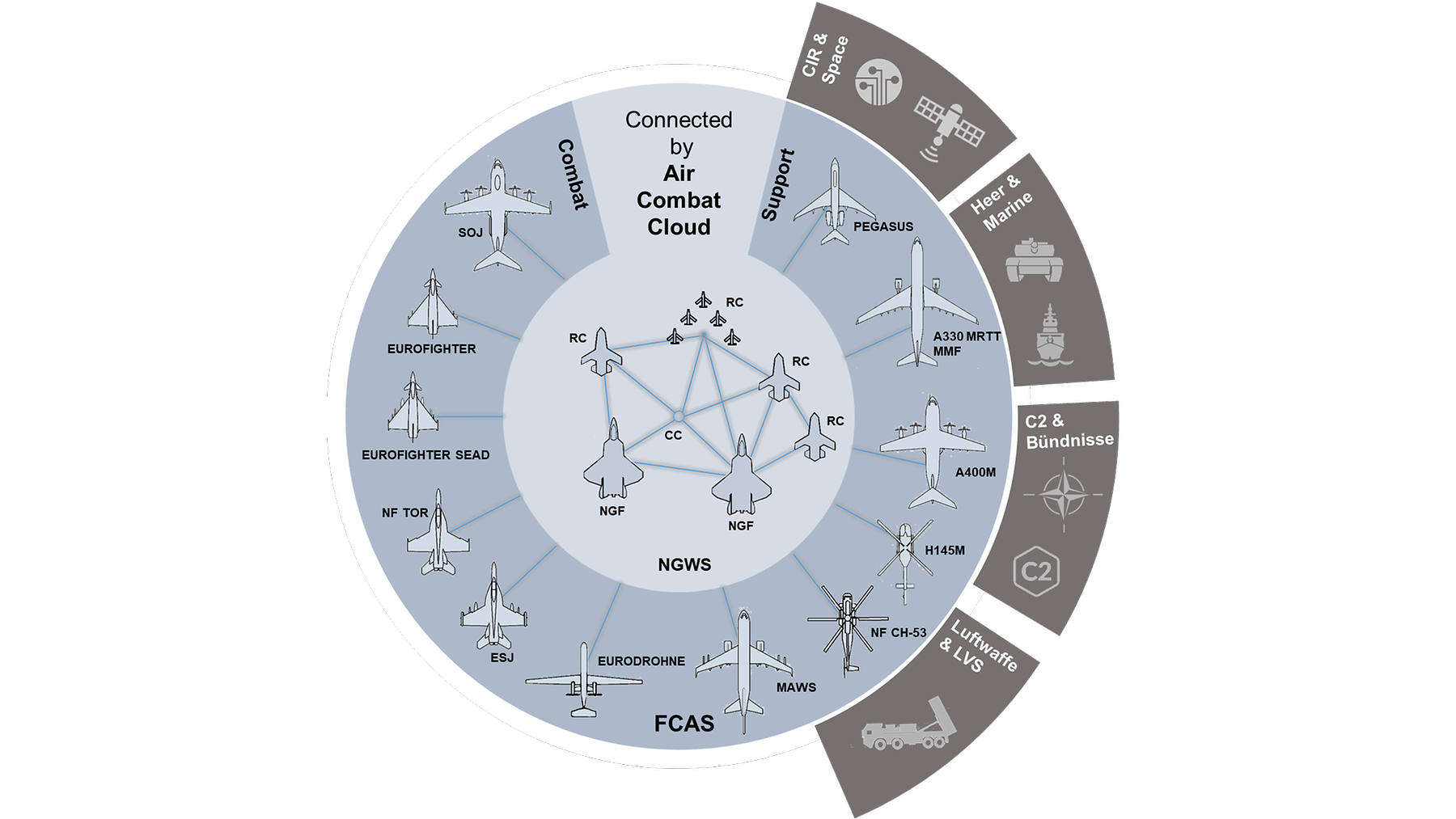

Airbus Defence and Space, in classic “everything’s fine” mode, emphasized ongoing work across FCAS technologies, including progress on sub-sections of the initiative:

- Remote Carriers – autonomous drones designed to support the manned New Generation Fighter (NGF), similar in concept to Helsing’s HX-2 drone wall.

- Air Combat Cloud – a secure tactical data network for mission coordination reminiscent of NATO’s evolving interoperable tactical links strategy.

“We remain fully committed to FCAS. The project represents an essential investment in European industrial cooperation and defence innovation,” Airbus said.

Still, observers remain skeptical—particularly as other joint ventures, like the Renk–NXP propulsion alliance, demonstrate smoother inter-industry collaboration.

Strategic Autonomy, Tactical Dysfunction: Can Europe’s Fighter Vision Hold?

FCAS isn't just another jet—it’s the flagship for Europe’s aspiration to secure its own military future. Launched in 2017, the program was designed to meet next-generation airpower needs and eventually replace both the Eurofighter Typhoon and the Dassault Rafale by 2040. The vision: a seamlessly integrated system of manned fighters, autonomous drones, and AI-enabled coordination—developed and manufactured independently across key European industrial hubs.

On paper, it’s a model of sovereignty. In practice, it’s beginning to fracture.

As individual countries move forward with parallel acquisitions—like Germany’s €763 million PAC-3 MSE missile deal or the high-profile F-35 buy—the cohesion around FCAS as a singular European defense platform is weakening. Each procurement decision chips away at the unified narrative that FCAS was meant to uphold.

Meanwhile, France’s Mirage 2000-5 commitment to Ukraine stands as a symbolic gesture of strategic independence—visible, patriotic, and ultimately disconnected from the larger FCAS trajectory.

The concept of “strategic autonomy” remains on the brochure, but its execution is increasingly defined by workaround procurement, consensus paralysis, and the tactical realities of working with three industrial egos in one cockpit.

“FCAS is a litmus test,” noted one analyst. “And Europe’s starting to sweat under the microscope."

U.S. Reliance and the European Balancing Act

The timing is significant. Germany is simultaneously pursuing high-profile procurement such as its F-35 acquisition, which some analysts see as hedging against FCAS-related risks, ie delay or collapse.

Read more on Germany’s evolving U.S. weapons policy.

While the United States remains NATO’s cornerstone, shifts in transatlantic dynamics—Trump-era ruptures, defense budget drift, and the rising appeal of procurement sovereignty—have pushed European states to rethink the cost of interoperability. FCAS was supposed to answer that. A European-built jet, flying without strings attached to Washington.

Instead, it’s become a study in the trade-offs of multilateral defense collaboration—some might say: in compromise engineering.

This dilemma isn’t limited to aircraft procurement. As NATO moves to integrate AI into command structures, it runs into the same walls. Concepts like cognitive command—where machine learning supports operational planning and coalition-level decision loops—, highlight the deeper fault line: grand coalition concepts, national-level mistrust, and the struggle to code consensus into software.

This theme also runs through German procurement: from air and missile defense systems like the IRIS-T SLM, part of the ESSI Sky Shield initiative, to AI-powered programs like Helsing’s HX-2 drone wall. Everyone wants autonomy—until they browse the U.S. catalog.

And so the contradiction persists: European defense wants to walk on its own. But right now, it’s still sourcing its laces from across the Atlantic.

What’s Next for FCAS: Phase 2, If It Survives

Negotiations over Phase 2—the interesting part with systems integration and a flying prototype—are now underway. But just like FCAS itself, they’re moving slowly and weighed down by unresolved issues over control and credit.

The FCAS outcome will shape how Europe approaches future defense programs, from AI-driven battlefield C2 to massive long-range capabilities like Germany’s shifting Taurus policy.

Or, as one French official allegedly said: “If we can’t agree on the cockpit, good luck agreeing on war.”

Explore Related Reporting: